*This article may contain product links which pay me a small commission if you make a purchase. Learn more.

Is the hit and run a smart play? In baseball, the hit and run has been around forever. But, it’s recently lost favor with coaches, especially now that sabermetric data is shedding light on outcomes in every possible situation. In this article, we’ll discuss this pros and cons of the hit and run, and whether you should be using it with your team (or cursing your favorite team for using it).

First: When is a Good Time to Hit and Run?

There are a few rules:

- Don’t strike a guy out (don’t hit and run on a 2-strike count)

- Don’t do it with a pitcher who is very wild and unpredictable, or who throws tons of breaking stuff

- Don’t do it with a hitter who swings and misses a lot, or who has bad plate discipline

And per those rules, hitting and running is best performed:

- On counts like 1-0, 1-1 or 2-1, where the hitter is more likely to get a fastball, and often a fastball away

- With a pitcher who has proven that he throws lots of strikes and likes to go away from righthanded hitters

- With a hitter who won’t miss a sign, and who has decent bat control

Got it? Those are three solid preconditions to think about. So, with that in mind, let’s look at some videos of hit and runs that worked and didn’t work…

A Perfectly-Executed Hit and Run

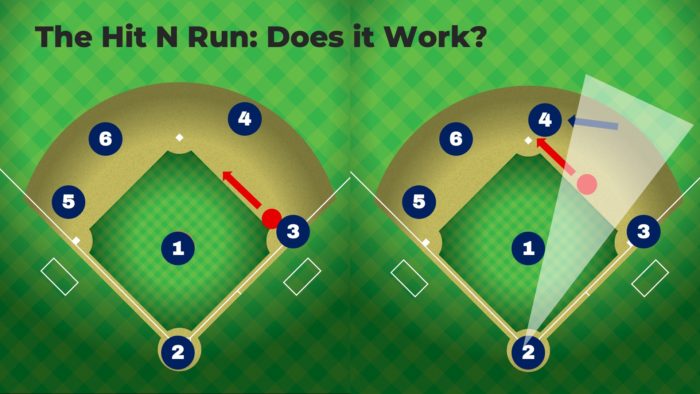

The runner steals, the second baseman runs to cover second base. The batter hits a ball to the right side of the field into the huge, vacant hole left by the second baseman.

This single sends the batter to first and the runner easily to third.

This is How Hitters are Often Forced To Swing:

Because the hitter must “protect” the runner, he is forced to try to hit any pitch to the right side.

Watch my video below with a full explanation of the benefits and negatives of the hit n run play.

Here’s what it looks like when it goes REALLY Wrong:

If the hitter swings and misses, or misses the sign and forgets to swing, the runner is a dead-duck at second.

The Pros and Cons of Hit and Runs

What’s good and what’s not so good?

[one_half_first]Pros

- Easy single

- Easily gets even a slow runner to third base

- Encourages a slumping or low-confidence hitter to swing

- Very deflating to the pitcher and defense when executed successfully

- Prevents a ground ball from becoming a double play

- Can give a weak hitter a big morale boost

- You look like a genius when it works

Cons

- When the pitch is in the right location, it’s easy. When it’s not…it’s very hard to execute

- You force a hitter to swing at anything, and put bad pitches in play

- You force a hitter to hit the ball to the right side, even when he might get a pitch he could drive for extra bases

- It can be frustrating and demoralizing for a hitter

- If the hitter misses, your runner is out by a mile at second base (usually)

- Requires both hitter and runner to receive the sign (often a big task in amateur baseball)

- Good baserunners go 1st to 3rd 50% of the time anyway on hit to the right side anyway

- Fly balls and pop ups can become double plays

- Line drives are almost guaranteed double plays

A Few Key Downsides, Explained More Deeply

#1. Who Knows Where The Pitch Will End Up?

The possible ending locations for any given pitch are vast, with only a small percentage of those potential pitches being ones that can be hit to the right side of the infield with relative ease.

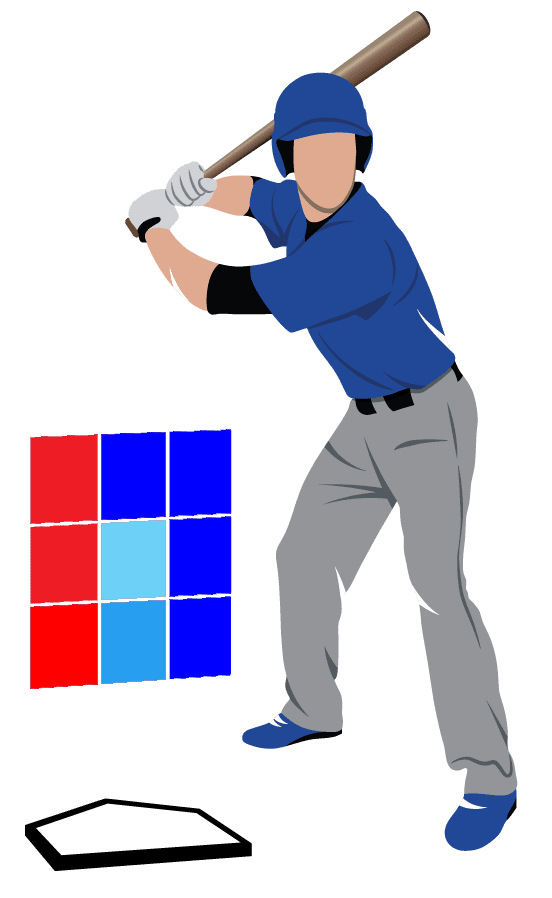

In the graphic below, the red blocks are pitches that a hitter can do the job with – hit the ball to the right side. But, as we all know, right-handed hitters (who represent 80% of all hitters) with swing flaws (most of them), tend to roll over pitches, which means that they ground outside pitches to the left side. So, even on the pitches that are easiest to hit to the 4-hole, its not that easy of a job.

Now, I know what you’re thinking, and sure – lefties have an easier time “doing the job” but still – they represent only 1 in 5 hitters.

And, a pitcher can throw the ball in any random location, either by choice or by error.

So, whats the likelihood that he puts the ball into the red zone above, AND the hitter does the right thing with it?

Pretty slim.

#2. Did You Spoil an Extra Base Hit?

By putting on a hit and run, you sentence the hitter to do one thing, and one thing only: hit the ball on the ground to the right side.

What if he gets a pitch middle-in, a pitch that he hits for extra base hits a high-percentage of the time? Well, the hitter must merely surrender to inside-outing that pitch, rather than demolishing it into the pull-side gap. Not to mention, the likelihood of hitting the ball to the right side on the ground on a pitch up, or inside, is very slim.

Was this what we wanted? To trade in a potential double or home run for a potential single? I personally don’t like to take the bat out of a player’s hands, so to speak, unless there’s a very strong reason we need to.

#3. Is the Risk Worth it?

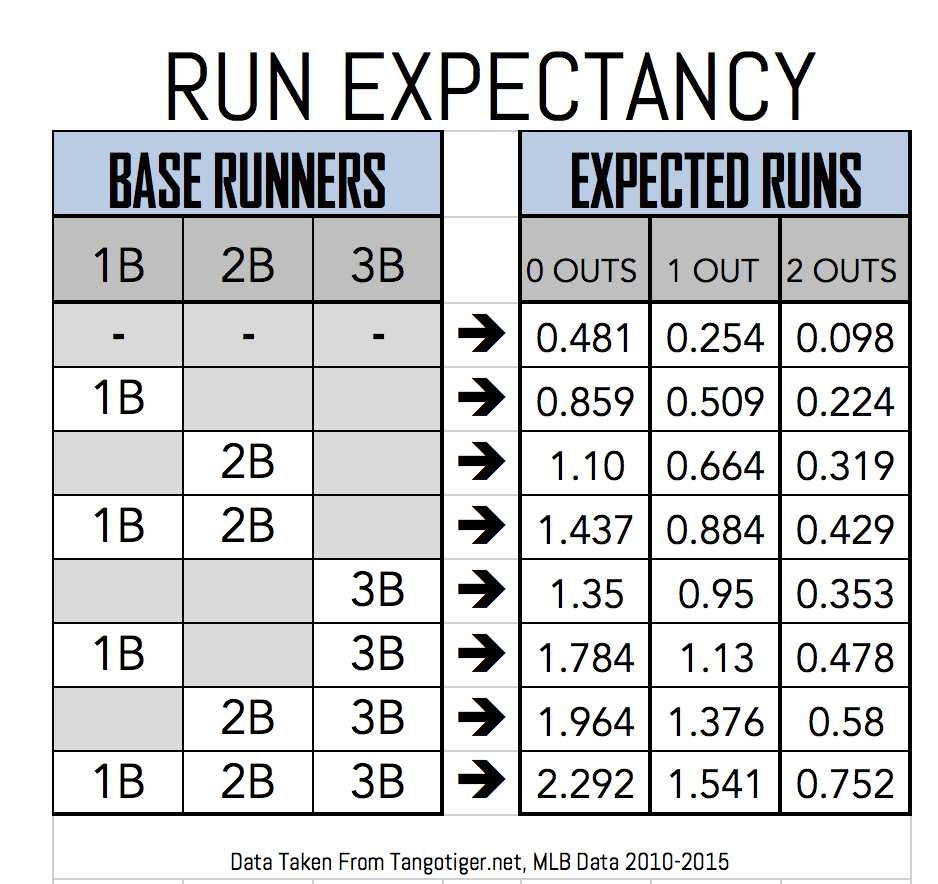

For this, lets go to the run expectancy chart.

For more information on run expectancy, I highly recommend The Book: Playing the Percentages in Baseball by Tom Tango and Michael Lichtman. It’s a solid read for stat-minded coaches and players.

Anyway, if we hit and run with a runner on 1st and no outs, we start with a run expectancy (RE) of 0.859 runs, meaning we expect to score 0.859 runs, on average, in that base/out state (fancy words for the situation).

Note: Some of the links in my posts earn me an affiliate commission. This doesn’t affect the price you pay, but I thought you should know. I only link to products or books that I’ve used, love and recommend.

Outcomes

[one_half_first]Good, Intended Outcomes

- Hit and run is executed as intended. Runners on 1st and 3rd, 0 outs. RE = 1.78 runs

- Net is +0.92 runs

- Ball is put in play, runner does advance. Runner on 2nd, 1 out: RE = 0.664

- Net is -0.20 runs

- Ball is put in play and the double play is avoided because the runner was stealing

- This essentially saves 0.57 runs.

Good, but Unintended Outcomes

The batter could also get a hit to another part of the field, or even an extra-base hit, but we’re going to leave those alone because they aren’t intended – though fortuitous – outcomes. Really, if a hitter lifts the ball, he didn’t do what he was supposed to do, even if the result was positive.

Additionally, the hitter can swing and miss while the runner steals safely, though that isn’t a typical outcome either. If the runner was competent enough to steal, he’d probably steal without the need to hit and run. Net is +0.24 runs when the runner steals successfully.

[/one_half_first]Bad

[one_half_last]But, if there are three potential negative batted ball outcomes:

- Ball is put in play, runner does not advance. Runner on 1st, 1 out: RE = 0.509

- Net is -0.35 runs (though this is the same as in a regular at-bat)

- Hitter swings and misses, runner is thrown out. Bases empty, 1 out. RE = 0.254

- Net is -0.60 runs

- Hitter hits a liner or fly ball is runner is doubled off. Bases empty, 2 outs. RE = 0.098

- Net is -0.76 runs

Overall Conclusion: Is the Hit n Run Smart?

We aren’t going to dive deeper into the numbers, but it’s clear that sometimes run expectancy increases, and other times it decreases as a result of a less-than-perfect outcome.

The real problem – that I don’t have an answer to – is how often a successful hit and run is executed. Given the difficulty in intentionally hitting a randomly-located pitch into only a small slice of the field…it’s safe to say it’s not that easy.

Avoiding the double play, and executing the hit and run as intended are the best possible intentional outcomes. And, I’ll just tell you that most amateur pitchers do NOT intentionally pitch inside very often, which does mean the intended location is usually away to right-handed hitters, who, again, make up 80% of all hitters.

But, the pitch with which a hitter can execute the hit and run properly may or may not come, and it’s with luck that a hitter gets that pitch. With any pitch that isn’t optimal, the odds of a bad outcomes – one that hurts the teams expected run tally – increases quickly.

And, when we remember that double plays – at the MLB level – are only converted 15% of the time they are in order, it may be an undue risk to take trying to avoid one. If 6/7 times we won’t ground into a double play anyway, why are we going to such lengths to avoid one? Certainly some hitters ground into a higher rate of DPs than others, but on average, they’re somewhat uncommon.

If good baserunners go first-to-third 50% of the time anyway, is there a need for so much risk to ensure a first-to-third outcome? I say no.

So, should You Hit and Run?

I’m certainly not going to say never. There can be a time and a place, and baseball situations are nothing without context.

When I was still coaching, we would not be hitting and running except in extremely rare situations, ones that are more related to the hitter and pitcher than the value of the play. But, that’s us.

We’d rather drive a pitch that is drivable, take a pitch that isn’t drivable, and go 1st to 3rd on singles by running the bases aggressively. The risk, for me and for us, is not worth the reward.

What do you think? Is hitting and running a valuable play? Let me know in the comments.